In 1971, I was only a child—yet that year has never let me go. It trails behind me like smoke. Always there.

I remember the freedom fighters, slipping like shadows through narrow paths between tin-roofed houses, drenched bushes and flooded rice fields. Swift. Silent. Certain.

Often, at night, Baro Amma would jolt me awake: “Get up, Get up—the guests are here.”

In the trembling glow of an earthen lamp, they appeared—armed, shirtless, soaked to the bone. Hungry, but grinning.

They ate fast, whispered ‘assalamulaykum’, and then vanished, crawling and swimming. Gone!

War seeped in like smoke—choking, slow, and relentless—into our tightly woven clusters of patriarchal families.

The news came with Bhai, our eldest cousin. He appeared at the edge of the yard, half running, half dragging his feet.

Issued the order: “Throw all the paddy in the pond.”

At first, no one moved. Everyone including the refugees from distant villages whose homes had been reduced to ashes blinked at him, stunned. The sacks were our life, our hope, our future.

“Why are you looking at me like that? The Army and the Rajakars are coming,” he said. “They know where the ration shops are. They know who has food.”

The sky broke open. All able hands came forward. One by one, the sacks were carried on shoulders, passed hand to hand, and dropped into the Mijibari pond at night. Hundreds of sacks of unprocessed paddy disappeared under the murky water.

Terror settled on us. A different kind of harvest was coming. We waited.

Girls had to be smuggled like contraband—into distant villages where the enemies would hesitate to trade.

Mothers wrapped girls in silence, in desperate unuttered prayers. They wore old, faded sarees that bore the scent of turmeric, home, and fear. No bangles, no anklets. The girls’ were ordered not to oil, comb and braid hair with ribbons. “Tie it in plain knots—no washing, no powder.” Some mothers kept their daughters inside dark rooms for days, as if that would make them invisible.

Ours was the first family to lay roots in this wild marshy land.

My great-great-great-grandfather etched our name into the soil with sweat and prayer—clearing jungles thick as folktales, driving out boars, and snakes that slithered like curses. On earth still pulsing with the breath of forest gods, he built a mosque: mud-raised, tin-roofed, humble as a prayer in the dark.

And so, Miaji Bari became more than a home—it became myth. A name the wind carried across jungles, newly ploughed paddy fields and gashing rivers, from mouth to mouth, until even strangers knew it by heart.

The Pakistani Army and their Militia Rajakars came and stationed in the suburban bazaar, three miles from our village. They had jeeps. They had Peace Committee collaborators who pointed out houses of Awami League supporters, Muktis, Hindus and girls.

Every jeep that didn’t arrive felt like both relief and dread. The anticipation gnawed worse than the event itself.

One afternoon, we heard, a group of Panjabi soldiers threw a six-month-old baby into the canal. They watched silently to see if he could swim. Then, they moved on.

Next day, the baby’s mother—stumbled back home, barefoot, drenched. Our uncle’s wife broke every rule, and ran into outer world, screaming like a hen that had lost all her chicks. But the girl said nothing. Didn’t cry. Her eyes fixed on her mother; she sank into the yard, knees buckling. Then slowly, silently, lay down.

Her body folded in on itself, like something returning to the womb. Frozen. Crushed. Unrecognizable.

And then—sixteen corpses on the dirt road, wrapped in torn grass mats, laid in a row across the crossing side by side. As if they had lain down in one final act of defiance, refusing to let the enemy’s vehicles pass.

That was our front line during Liberation War: no tanks, no uniforms. Just resistance, laid bare.

Each morning, we waited for a voice—the BBC, crackling through short wave radio. Did the world still remember us? That 75 million in East Pakistan had been denied their mandate—colonized in all but name—and so declared independence? That elected representatives, along with Hindus, Muslims, Christians, ethnic minorities, all, were now being hunted?

Did they know thousands were dying each day?

The first man we knew tied to the British crown was a havildar in the East Bengal Regiment, Great-grandfather of someone in a distant village.

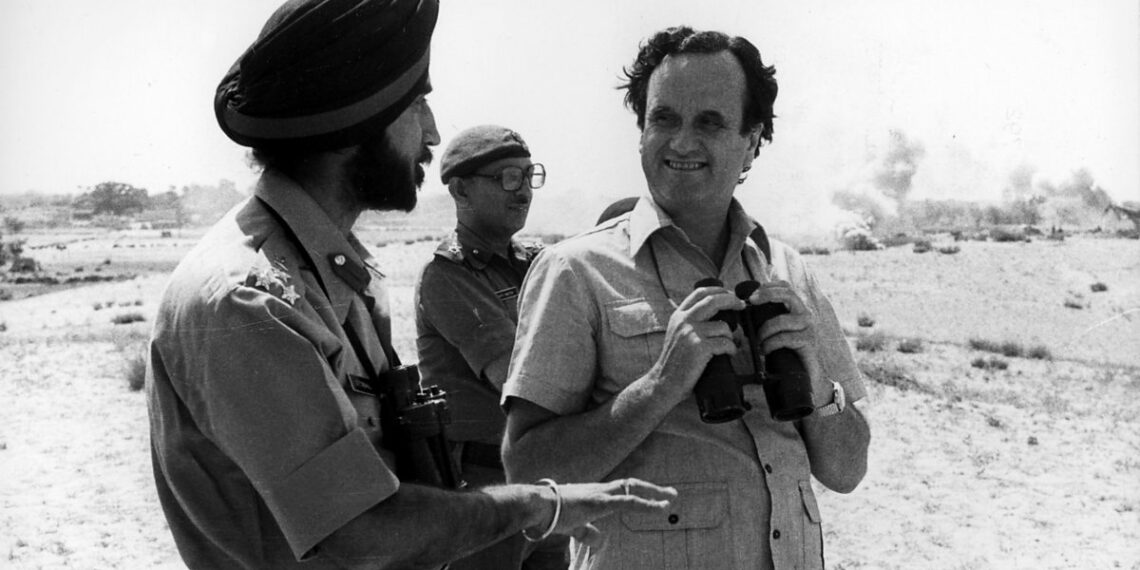

The second was Mark Tully—a British journalist reporting from Delhi while our land was soaked in the blood of millions. The Ganges Padma ran thick in the rust of ruined lives, its silence tinted red as it flowed downstream. Along the river banks, white bone like drifting sands piling, shaping a new delta.

Radios were rare sacred artifacts in our village. Men and boys crowded the yard; women stood in doorways, veiled by shadow. Children clung to their mothers’ saris. The radio sat like a deity on a stool beside our uncle’s easy chair.

Shadhin Bangla Betar Kendra, Akashbani Kolkata, and the BBC gave shape to the apocalypse around us.

We grasped the collapse of our world through the words they chose. Truths and lies—what other nations thought or pretended to know about us—flowed to us like wind from the storm’s edge. We were at the cyclone’s eye.

If the British voice inside the box spoke of our fighters, we grew tense with hope.

If the Pakistan Army’s bulletins lingered, we despised the broadcaster.

One blackout night, I saw a father crouched beneath a wooden cot, radio slung over his shoulder, arms spread to shield his motherless children. He whispered, “Hush! Shabdo koro na. Don’t make a sound!”

Outside, gunfire tore through the darkness.

By dawn, a soft crackle stirred me awake. I dashed outside to count the bullet holes in our wooden wall. On the other side, people gathered by the marshy land where the railway sliced through. A young man lay supine upon the earth’s soft rise—his arms stretched wide like swan wings in mid-flight. His milk-white shirt soaked red. Was the water red too? I don’t remember. But his feet—twisted unnaturally—were half-submerged in the water pooled at the foot of the incline.

Father found me and then walked toward the gathering, the radio made a soft crackle, and then a distant male voice — calm, measured — came through.

I ran after Abbu. “This is the BBC World Service. Today is”…Mark Tully’s voice drifted gently into my ear.

The listeners did not listen. They themselves were the witness by then. The young man had graduated with my eldest brother.

Fifty-four years later, it’s different.

It no longer feels like a witness.

It sounds like an echo shaped by others.

(To be continued)