The flight from Imphal to Dibrugarh lazed over a fog-filled runaway. The clouds were refusing it to touchdown and the moustachioed Maharajah flirted with the clouds that had gathered to welcome us. I sat back bemusedly “unaware” of the Air India captain’s announcement that “we have just 30 minutes fuel left…we’ll circle over Dibrugarh and attempt an approach once the visibility is better”. Indeed, the visibility—as one could fathom from Aisle seat myopia was next to nought.

I could sense the consternation in some of my Economy Class fellow passengers. Perhaps the “helmsman” needn’t have confessed about the fuel that the aircraft was left with or the lack of visibility. But long years of being on long haul flights—over the Pacific and Turbulence—had steeled my commuter conduct. I remained smug.

I thought about the Phumdis that I had seen from the helicopter flight from Imphal to Churachandpur instead. Dotted disk-shaped, spring green speckled with Khangpoks—I didn’t recall seeing Sangais dancing—were enough to keep my disquiet about the Captain’s grave announcement at bay.

But I did become a little concerned about the Liaison Officer and the entourage that was waiting for me in Mohanbari airport. They were to escort me to Lekhapani and later to Miao.

Indeed, the second leg of my eastern sojourn had just begun.

It had begun from Guwahati via Jorhat to Mon, and thence to Oting, back to Jorhat and heading for Kohima—via Col Vikrant’s lunch—to Kohima where Maj Gen Vikas Lakhera sought my safe arrival.

I am a Rimcollian. But for my ill-gotten hypertension the medical specialist in Bhopal would have shooed me off to the National Defence Academy. It was a sad June day: the Year of our Lord 1983. The ‘Best Scientific Boxer” in me—in RIMC that year—has never quite comprehended as to why my “Systoles” had militated with my “Diastoles”.

Earlier in Pratap Section in Dehra Dun I had even dreamt of Hunter Squadron and Camp Rover and how my vision of being an Assamese cadet would fit with the regime. But the verdict of a stethoscope and a serpentine providence had other plans for me. I was destined to meander a different alleyway past Yamuna, Potomac, Yongding, Seine, and in later years even the Siyom, Noa-Dihing, Lohit and the Namka Chu before I reached my keyboards. Reverie had taken me to forty years ago.

But it was time to land. The clouds over Dibrugarh had cleared well in time for the Air India Captain’s fuel to be replenished.

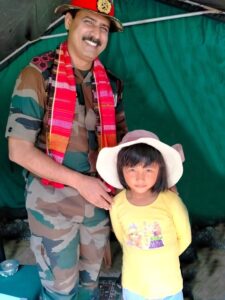

I was now in the land and the hands of Brig Swarn Singh, Vasisht Sewa Medal, Commander of the 25 Sector of the Assam Rifles.

I have met many an Indian army commander but the gravity, modesty and poise of Brig. Swarn Singh were humbling and endearing.

I had spoken and corresponded to the officer for three long months about a visit to his “Area of Responsibility”: each time “something back home”, indifferent health and even clouds overhead had interfered. But on 7 October 2023 I was finally meeting the officer who—I felt—was patiently waiting my nomadic roundabouts to end.

He was a matter of fact officer. His briefings were brusque and to the point. He knew his terrain and also the terrain mapping that I sought. What’s more, he knew the affinities and the hostilities that criss-crossed his land. The new aspects that brought to bear the neo-politics of the land pertaining to Singphos, Chakmas, Noctes, Wanchoos et al that awashed the green of the Noa-Dihing.

Tirap, Changlang and Longding are three districts of Arunachal Pradesh that are heir to much more than meet the regular eye.

Way back in 2001, I had visited the same HQs for a security briefing and had a few days later footed it—when my leg was in one piece—to the far cranny of Lekhapani’s “AOR”. The briefing by Brig Swarn Singh brought back memories of two decades ago. I recalled from over two decades ago.

Tirap and Changlang area of Arunachal Pradesh (Longding was combined to the “Triangle of Concern” later) is a region which geo-strategically connects Assam, Myanmar and Nagaland. It is also a region that lends itself to the trans-border insurgent agenda and showcases a motivation, strength and concern, which stem from subterfuges that allow a level-playing field to various anti-India organisations.

I have undertaken multiple visits to the region and have witnessed to the manner in which the expanse lends itself to (a) the cross-border agenda vis-a-vis India and Myanmar (b) geo-strategic engineering by the NSNK (K), ULFA, affiliated groups of the NSCN (K) and, as I was informed by Brig Swarn Singh, even the NSCN (IM). The conduit is extremely novel and was it not for the Assam Rifles the corridor would have been a veritable “grazing ground” for anti-India agenda of every hue and sort.

I kept entries a diary—from 2001—even as I was patrolling with the Assam Rifles in the two districts. Excerpts from the pages from the diary are being reproduced for the reader to comprehend the real manner in which the NSCN (IM)’s usage of Christianity by way of what it terms as “Op Salvation”.

It was 0545 Hrs when the Assam Rifles Company— which I was following—entered Pongchou Village. The climb to the village was steep, a good 45 degree gradient. The Company Commander told his men to keep their eyes peeled on the overhanging cliffs—we were apparently negotiating an area where we could have come under militant fire. It had been reported the previous night that the “Naya Party”, the name by which NSCN (IM) is known in Tirap and Changlang as opposed to NSCN (K) which is the “Purana Party” had been seen in the vicinity. But, the young captain assured me that ambushes on the Indian army by the NSCN (IM) were few and far between. It was a more likely possibility that they would spirit away at the sign of our approach. Indeed, he sought my attention to the tom-tomming that was emanating from the village. It was, I was told, a message for the militants, to warn them of Indian army presence. Later, one of the Indian army jawans brought me the bamboo receptacle that was sending out the “message”. It was a fine homemade instrument and I could imagine the timpani it sent out across the cliffs, warning the “Naya” and “Purana” Parties that it is time to decamp.

The Pongchou Village’s church greeted us. But for its largeness and the cross on top that indicated that we were on hallowed grounds, it looked like an ordinary hut. Only the “Raja’s” hut was bigger than the church. The “Raja” invited us into his hut, it was rather dark and some sort of meat was being smoked in a corner. The “Raja” could speak Assamese. I asked him about the “Parties”. He reluctantly agreed to the fact that the “Parties” were visiting them, but would not be drawn into a discussion about what they sought (a Ranapio—a person who acts a “go-between”/dak runners/informer—later told me that the “Naya Party” had been good to the villagers, teaching them about hygiene). The “Raja” also told me that it had been days since the “parties” visited his village. We were getting ready to leave when a man entered the “Raja’s” hut singing hymns. He was the village pastor. In fluent English, he told us that he had come to the village a couple of years ago (after he graduated from the University of Delhi) to spread the word of Christ. He told us that he had settled in this village, having wed all the daughters of the “Raja”. He was also a Naga.

Although a communal statement is not merited at this point, the fact of the matter is that the NSCN (IM) had (at the time)—instituted a novel method to “include” Tirap & Changlang into their Greater Nagalim. The phrase they used was “Op Salvation”, and conversion to Christianity was one of the stratagems. It has succeeded, too, as was evident from my diary entry above. Almost every village had a Naga pastor, who was also invariably the “Raja’s” son-in-law.

In Pongchou Village, the Naga pastor had married all the daughters of the “Raja”. It reminded me of the Mel Gibson blockbuster “Braveheart” where there is a scene which shows the King of England, Edward I “Longshanks” telling his generals about enforcing Prima Nocta, the “privilege” of English Noblemen to sleep with a woman on the first night of her marriage in an attempt to breed the Scots out instead of fighting them out.

The NSCN (IM), therefore, is trying to elbow itself into areas where it would provide it the depth engineering it seeks. The organisation’s efforts in Arunachal Pradesh have already showcased the methodology.

In Dima Hasao and Karbi Anglong of Assam it has a tacit understanding with the militant outfits operating in the area, and there was a “Hebron Agreement” some years ago between Dima Halam Daogah and the NSCN (IM). But inclusion of areas in states outside Nagaland will not be easy: the communities that are sought to be forcibly termed Nagas would resist it, as would the dispensations of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam and Manipur. A resolution to the problem that characterises the Naga issue is, therefore, not going to be one that can be ushered in with ease.

But the fact of the matter is that Brig. Swarn Singh and his IG, Maj Gen. Vikas Lakhera had changed the narrative. The NSCN (IM)’s attempts to cross over from Nagaland’s Mon onto Arunachal Pradesh and import their Op Salvation had been almost put a definitive stop to.

The sinister corridor that was being used by the insurgents from Myanmar, too, had come to a virtual end. Yes, there were camps across in the Sagaing Division of the strife torn country, but the inmates of these anti-India scheme of things were either being worn-out or being pushed to desertions.

It is now time that far-off “sunrise” thought in New Delhi found ways to pave correct pathways to Vijaynagar, where the “Sentinels of the East”, the Assam Rifles are the first to greet the Indian sun.

It would also soon be one of the foremost of places for visitors from lands afar to the enchanted frontiers. Brig Swarn Singh’s and my tour to Deban and beyond with him had already established that cheerful augury.