Not many years ago, a Bangladeshi newsman once associated with the BBC’s Bengali Service gave a new twist to Bangladesh‘s history through a letter to The Guardian newspaper in London. He was responding to an article by Ian Jack on Bangladesh. At this point, note what this Bengali gentleman had to say about Bangabandhu’s arrival in London on January 8, 1972 following his release from Pakistani detention by the government of President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

On his arrival at Heathrow, said this long-time BBC broadcaster, Bangladesh’s founding father was received by Apa Panth, the Indian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom. When Panth addressed Bangabandhu as “His Excellency,” Sheikh Mujibur Rahman appeared surprised. To all intents and purposes, he had thought that he had been freed by the Pakistan government after full regional autonomy had been granted to East Pakistan. He had absolutely no idea, implied the veteran broadcaster, that Bangladesh had become a free country. And that was not all. This journalist also peddled the untruth that he was the first Bengali to meet Bangabandhu once the latter had checked in at London’s Claridge’s Hotel.

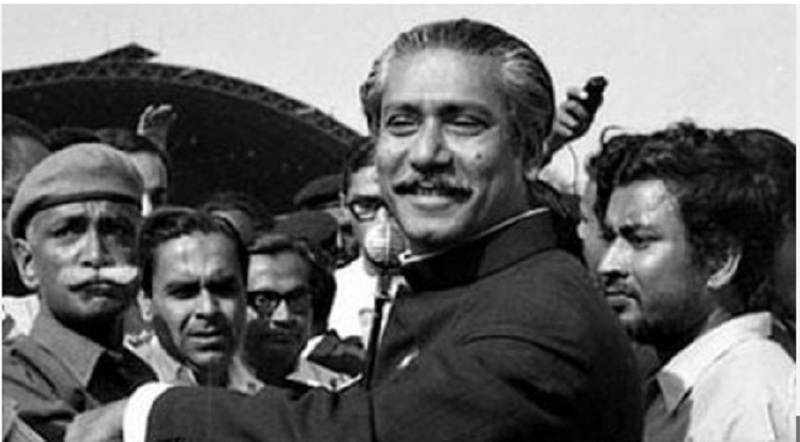

That letter in The Guardian was proof once again of the persistence with which Bangabandhu’s detractors –and sometimes his followers — have been trying to undermine his place in history through their imaginary tales and concocted stories. Let the record of Bangabandhu’s arrival in London in January 1972 be set straight.

At Heathrow, the Father of the Nation, accompanied by his constitutional advisor Kamal Hossain and Hossain’s family, was received by Ian Sutherland, a senior official at Britain’s Foreign Office. Also on hand was the senior-most Bengali diplomat in London at the time, M.M. Rezaul Karim, with his colleagues Mohiuddin Ahmed and Mohiuddin Ahmed Jaigirdar.

In his account of the day’s events, Karim, now deceased, left behind a clear narrative that no one has questioned till now. Bangabandhu hopped into Karim’s car (and Karim himself was at the wheels) rather than take the limousine the British government had placed at his disposal and on the way pelted the diplomat with endless questions about the just-concluded War of Liberation. Crowds of Bengalis began to gather before Claridges Hotel once word began to get around that Mujib had arrived there. Our veteran journalist happened to be one of many who turned up there.

Hours later, Bangladesh’s leader spoke at a crowded news conference at the hotel on the matter of his imprisonment in Pakistan and the manner of his release by the Bhutto administration. Prior to the news conference, he had spoken to Prime Minister Edward Heath and Opposition Leader Harold Wilson, the former at 10 Downing Street and the latter at Claridges. Bangabandhu had also spoken to Prime Minister Tajuddin Ahmad and Begum Mujib and the rest of his family as well as Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, soon after stepping into Claridges.

His performance at the news conference was a clear demonstration of his command of the situation. Besides, his meetings with Bhutto between the end of December 1971 and his release on January 8, 1972 were crucial: Bangabandhu had been informed by Bhutto of the new realities in the subcontinent, of the fact that there was a government at work in Bangladesh, of the fact that Indian troops were in the new country. The Pakistani leader wanted, though, guarantees from Bangabandhu that Bangladesh would maintain some kind of link, even a loose one, with Pakistan. Bangabandhu made no response.

And that is the story of January 1972. But when you seriously reflect on the many ways in which certain individuals have endlessly tried running Bangabandhu down, you cannot but be appalled at the depths to which they have gone to denigrate him. There are yet Bengalis whose sense of history and understanding of Bangabandhu’s political career come across as pitiably poor. They will raise the question of why Bangabandhu ‘surrendered’ to the Pakistan army in March 1971. It is then that you are compelled to remind them that Bangabandhu’s politics had always been based on constitutionalism, that fear was never a part of his character, that he did not have it in him to run for his life.

In this country, we have had men, some of them well-known freedom fighters, who have gone around screaming their refusal to honour Sheikh Mujibur Rahman as Bangabandhu. When they do that, you ask them a couple of questions: If you do not honour Bangabandhu, why did you join a war that was waged in his name? And, more significantly, when an entire nation calls him Bangabandhu, who gave you the right to deny him his place in our consciousness and in our history?

There are then a few others who have sought to profit through alleged association with Bangabandhu. A veteran Bengali journalist settled overseas once penned a book on his closeness with the Father of the Nation about three decades ago. You would think, as you go through the work, that this newsman was the only individual in Bangladesh to proffer words of wisdom to Bangladesh’s founder.

He informed us, to our disbelief, that in the late hours of the night and buffeted by crises, Bangabandhu would seek his advice, call him and ask him to come over to 32, Dhanmondi. Of course, nothing of the sort happened. There is then the story of another individual (and he too lived abroad till his death) who tried convincing people that in the heady days of March 1971, he was press secretary to Bangabandhu. His assertions were never verified. No one recalls him holding that position.

Today, as an illegal, unconstitutional and unelected regime presides over the destruction of the history and heritage of Bangladesh, it goes into overdrive to demolish Bangabandhu’s iconic 32 Dhanmondi home and every symbol of the War of Liberation, it becomes the sacred responsibility of every Bengali to resist these internal enemies of the State. As we recall this historic day in January, when the Father of the Nation flew to freedom after nearly ten months in prison in militaristic Pakistan, it is time to reassert the old spirit of nationalism in Bangladesh, time to inform ourselves and our children and grandchildren of the power that has always underscored the spirit and electric appeal of Joi Bangla.

ALSO READ: Bangladesh: For the BNP, politics post-Khaleda Zia

It is time for all secular forces in Bangladesh to come together in the new battle for Bangladesh, for the country led to freedom by Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman to be taken back from those who have commandeered it, from the little men and women playing havoc with the idea that went into the creation of Bangladesh.

On January 8, 1972, history was in full play. Bangabandhu was coming home. Destiny was ours to shape.