In the third week of March 1997, about 40 followers of the American Heaven’s Gate cult, fully brainwashed by their leader Marshall Herff Applewhite on a crazy “mashup of evangelical Christianity, New Age practices and UFOs”, took to mass suicide.

This was among the strangest episodes in the history of American cultic practices and beliefs: apparently rational human beings taking their own lives by overdosing themselves on a “toxic cocktail of barbiturates and alcohol” in the belief that they would graduate to a higher life even as they escape this earth on a UFO.

Before their final destruction, Applewhite (aka “Do”) would often tell his followers and hand out dates of the arrival of the UFO. Quite obviously, there would be no UFO.

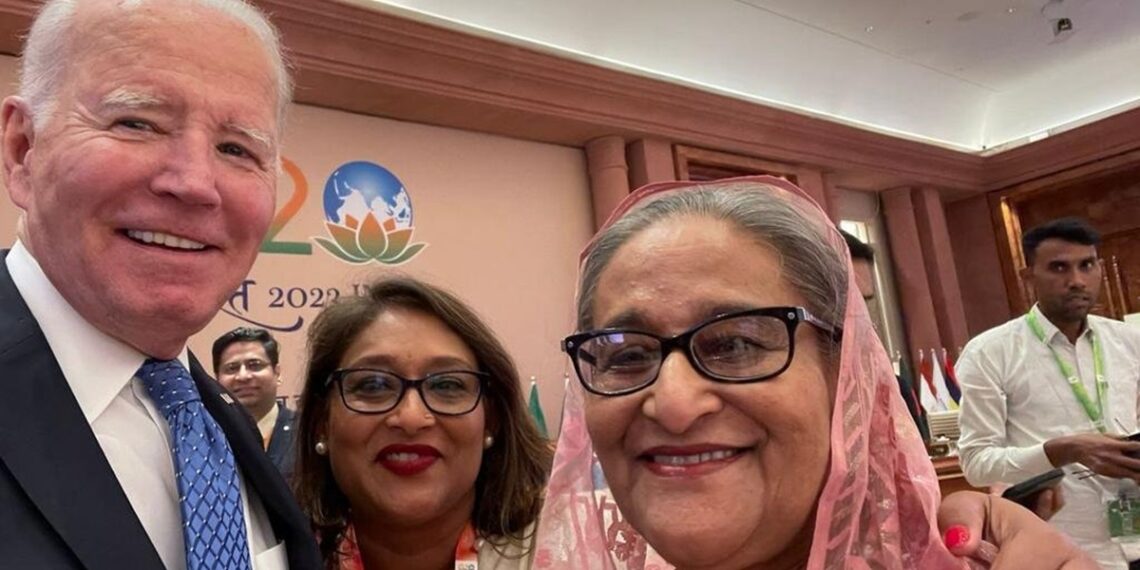

The Joe Biden administration’s promise of ushering in democracy, human and labour rights and the right to vote in Bangladesh – articulated and delivered by the likes of Donald Lou, Uzra Jeya, Afrin Akter and finally Peter D Haas – is not very different from Applewhite’s assurance of the UFO’s arrival.

Here is the long and short of the US ‘game’ in Bangladesh: it was an elaborate ruse to dupe Bangladeshis of all hues – the people in general, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and its political allies, human rights activists and believers in democracy – who actually got taken in by the Biden administration’s putative “values based” international relations approach.

There were two other willing partners in Washington DC’s ‘game’: the Indian establishment and the Awami League.

It all began on October 28 when the Sheikh Hasina-led Awami League contrived the violence in Dhaka and to accuse the BNP and Jamaat-e-Islami for it. The ‘set-up’ was good enough to put away the BNP’s top leadership and thrown in jail over 20,000 party supporters across Bangladesh.

This politically charged and volatile situation also created the ground for the Americans to raise their pro-democracy, pro-human rights and pro-labour rights pitch. There was a flurry of visits by Lou, Jeya and Akter to Dhaka where they met senior government functionaries.

And on each occasion, it was quietly let out that the American aim was to ensure “free and fair” elections in Bangladesh. It was only much later than “violence free” elections was added to the Americans’ so-called wish list.

Now, recall the subsequent violence that involved Bangladesh’s garments workers, followed by Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s open declaration that the US would deploy its “tool kit” of measures to correct the anomalies and shortcomings in the country’s labour rights and laws.

The American administration’s vocal propagation of “values and rights based” engagement with countries with democracy deficits was ably followed on the ground – Dhaka – by the redoubtable Haas who went around meeting senior leaders from the Awami League and the Jatiya Party to drive home the point that Washington remained firm on free and fair elections.

A one-page statement, signed by Lou and Haas, was shared with these leaders as also the BNP. This referred to the urgency of holding dialogue between political parties and reminded the leaders that the visa restriction policy – a veiled indication of likely trade and other sanctions in the future – was in operation. The lie had to be repeated many times over for it to impact Bangladeshis.

Haas then flew out to Sri Lanka, ostensibly to enjoy a Thanksgiving vacation. But did he secretly meet with Indian officials there or in India? This still remains a mystery as does his Christmas sojourn in Mumbai.

However, what could not be kept a secret was his meeting with senior Indian Ministry of External Affairs officials in New Delhi. But, of course, no one was any wiser on what was discussed during these clandestine meetings.

After Haas’ return from Sri Lanka on November 28, there was much expectancy in the air of likely US sanctions against a recalcitrant Dhaka. Again, by way of careful plants, the US embassy in the Bangladesh capital let out inspired whispers (in private conversations with local interlocutors) of punitive measures against the ruling Sheikh Hasina regime and that America will not budge from its demands. Earlier, there was no action when the election dates were announced on November 15.

It was when Haas returned to Dhaka from his India visit, with no visible or even distant signs of any punitive action against the Awami League regime, that doubts began to crop up in the minds of influential Bangladeshis about US intentions. Many sniffed – now rightly – a deal.

The objective, however, was to keep the sanctions pot boiling and allow the whispers to seep deep into Bangladeshis’ collective psyche. On their part, Awami League leaders, speaking both publicly and privately, reminded the people of “impending American sanctions”. And thanks to social media, this perfidious campaign – as if this was the ultimate truth – spread like cyber-fire.

New Delhi too played its part with aplomb, taking the view (on November 10) that the elections were Bangladesh’s internal affair while obliquely referring to its support for the Awami League regime. Indeed, India and China’s position were similar if not identical. In December, India pulled out all stops to convince various American pressure and interest groups to convince the US establishment to go easy on Sheikh Hasina.

The doubts of late December 2023 turned into conviction by January 10-12 when no American punitive measure was announced despite a completely rigged election. The American ruse could no longer be kept a secret when Haas met Bangladesh’s newly-appointed Information and Communication Technology Minister Zunaid Ahmed Palak on January 15, followed by a rather warm meeting with Foreign Minister Hasan Mahmud on January 17.

Suddenly, the US’ so-called lofty principles of “free and fair elections”, restoring democracy, human rights and labour rights are not part of the narrative post January 7, 2024. The American ruse was so complete and full that many in Bangladesh still believe that “something may yet be in the offing”. The actual lie lingers on long enough to sound like truth.

It is a matter of time before the Washington-Delhi-Dhaka deal, involving global business and regional security interests, begins to be unraveled in all its cynical details. With its leaders still in jail and thousands of its supporters lodged in prisons across Bangladesh, the BNP will find it difficult to regain its political USP. More importantly – and this is no dark secret any longer – the BNP, which relied heavily on the US, may not be able to trust the Americans, including Haas, in the foreseeable future.

The “stolen election result” could also cause an implosion within the BNP in the months to come.

And what of the US? Bangladeshis who placed their explicit and implicit trust on the US, will turn their backs on a power for which the call to restoring democracy, human and labour rights, besides other so-called “values- and principles-based” policies, will sound increasingly hollow. Suddenly, after his meetings with Palak and Mahmud, Haas did not repeat the earlier “free and fair election” homilies. For all was really pious sermonising and bandying about platitudes.