Bangladesh is in a bind. Behind all the window-dressing and tall claims, the economic situation is deteriorating thereby adding up to the political uncertainty.

Once a stable, growth-oriented economy, the country is now dependent on the International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailout.

Growth projections are taking a nosedive. Inflation rules at double digit, without much prospect for softening, and food prices are ruling higher.

Politically, the Dr Muhammad Yunus administration leaned towards estranged parent Pakistan. Hopefully, Bangladeshi economy will not become a replica of Pakistan that survives on one regular dose of IMF bailouts. (Pakistan had 22 bailouts in 77 years. The 23rd bailout is on course)

If Dhaka survives, the credit should go to India-Bangladesh economic ties. Data shows, rising supplies of food and other essentials from India, kept Bangladesh going over the last four months.

A dangerous cocktail of slow growth and high inflation is making Bangladesh increasingly vulnerable. While releasing the fourth tranche of the ongoing $4.7 billion loan assistance in December, IMF lowered the growth projection for 2024-25 (July-June) fiscal year from 4.5% to 3.8%, lowest since the covid year of 2020.

In October, IMF elevated the inflation predictions to 11% for the fiscal year. The food inflation touched 14% in November.

The multilateral agency stuck to the elevated inflation projections during its December review.

Inflation and instability

Inflation is critical for political stability of any country, more so for a poor country.

Sustained high inflation for nearly two years was the root cause of the popular dissent against Sheikh Hasina government in Dhaka. The economy was weakened during covid.

Global volatility following the Russia-Ukraine crisis exposed it to serious risks. Export revenues dropped but import costs went up to create a deadly liquidity crisis.

Bangladesh is hugely dependent on imports for almost anything and everything. Nearly 85% of its export revenue is generated by readymade garments exports. The raw materials (cotton and manmade fibre) are imported from India and elsewhere.

According to Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (Statistical Yearbook, World Food and Agriculture, 2023), Bangladesh is the third largest food importer in the world.

Low demand in major destinations and cost push had hurt garments industry. Growth and income suffered. Import restrictions pushed inflation. Hasina tried to maintain liquidity in the local market by printing money which added to the inflationary pressures.

Last but not the least, the government tried to keep the sentiments up by presenting fictitious export numbers.

Yunus fudging numbers?

Hasina is now history. But Yunus administration failed to make any positive change in the economy in four months of stay. On the contrary, the situation is worsening. The inflation has intensified. During Hasina’s rule inflation was ruling just below 10%. Now it is in double digit mark and has been rising for last three months.

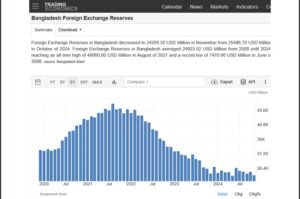

In four months, the government printed Taka 225 billion fresh currencies. The foreign exchange reserve is consistently declining since July and is now close to the 10-year low recorded in May 2024. The reserve will increase with a fresh IMF injection of $645 million.

Clearly, the liquidity crisis is intensifying in Bangladesh but that didn’t stop the Yunus administration from making audacious claim of 20% year-on-year export growth in October and 15.6% in November. The claim is far from believable.

Firstly, media reports suggest 130 garment manufacturing units stopped working in September due to issues ranging from liquidity crunch to labour unrest. While production resumed in October, the immediate spike in exports is questionable. Can a sector recover and grow at such a pace after significant disruptions?

Second, Bangladesh imports majority of cotton (fabric and yarn) from its next-door neighbour and secondlargest trade partner, India. Delhi also meets a substantial part of Dhaka’s energy requirements.

Data available with India’s commerce ministry shows energy exports to Bangladesh remained flat or marginally lower. Bangladesh’s import of cotton dropped by a whopping 12%. Can industrial activity zoom without energy and raw materials?

Third, the vendetta politics pursued by the ruling dispensation has thrown at least three top groups – Beximco, S Alam and Gazi – out of operation. All were affiliated to Hasina’s Awami League.

Beximco is the largest manufacturer. S Alam controlled 20-25% of international trade. As per media reports, together they laid off at least 50,000 employees. The impact will be wider on indirect employment. Factories closed, people are losing livelihood and exports rising – Is this believable?

Food from Delhi

What is necessarily happening is clear from India’s trade data with Bangladesh. A cash-starved, recession hit Dhaka is importing less of industrial products and more of food essentials to combat rising inflation. India reported 2.5% growth in exports to Bangladesh in October and 2.85% growth during April-October. This is largely driven by edibles.

As in October, India’s egg exports to Bangladesh is up by over 450%, potato and onion exports grew by 47%, spices by 28%, rice and wheat by 93%, sugar 100% etc.

Incidentally, India was seventh-largest export destination of Bangladesh, significantly ahead of China, in 2023. It was ranked 15th a decade ago. As in October, Bangladesh’s export to India was up by 10.6%.

ALSO READ: How India can help check rise of Islamists in Bangladesh

The exports were up by a marginal 1.12% for April-October. Interestingly, India’s import basket from Bangladesh has less of textiles (40%) and more of other products. That explains the importance of India-Bangladesh ties in such difficult times.