Politics has been getting intense in Bangladesh. The Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) has demanded elections by July or August this year.

The statement is in contrast to the position of the Yunus-led interim government, which has gone on record with its view that elections could be held either at the end of this year or early in 2026.

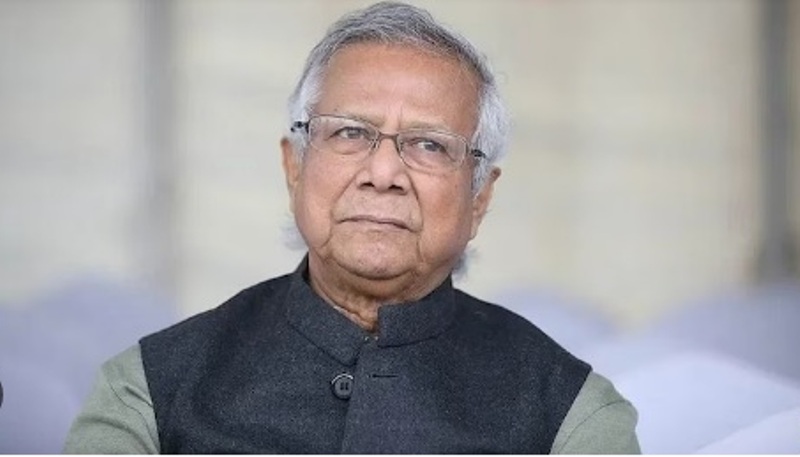

Given Bangladesh’s volatile political history, it is quite conceivable that in the weeks and months ahead, pressure could grow on Muhammad Yunus to announce a roadmap to elections as a way of power passing into the hands of an elected government.

There is little question that the Yunus regime is in a difficult situation at present. And yet when he took charge of the country in the aftermath of the fall of the Awami League government in August last year, the public expectation was that he would be able to steer politics to a new phase by clearing the decks for fresh, free and fair elections to be organised.

As a Nobel Laureate, he was the repository of the nation’s respect. It did not help Sheikh Hasina’s government that it engaged in vituperation against Yunus and towards the end of its rule sought to humiliate him by having him placed in court in a cage.

Professor Yunus was for many a symbol expected to be a fresh beginning for the country.

Unfortunately, there have been mistakes, which have occurred on his watch as Chief Advisor of the interim government.

When he took over three days after the departure of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina from the country, it was the popular expectation that he would condemn the vandalism that had resulted in the destruction of Ganobhavan, the prime ministerial residence, and the torching of the museum dedicated to Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the founder of Bangladesh assassinated with most of his family in 1975.

Yunus did not condemn the vandalism. Neither did he feel it necessary to visit Bangabandhu’s home nor his grave at his Tungipara ancestral home as a mark of respect to the Father of the Nation.

It was a mistake that ought not to have been made. It was quickly followed by another, when Yunus told the VOA’s Bengali Service that a reset button had been pressed in Bangladesh through the students’ movement against the Hasina government, implying that the country’s past was irrelevant and the future was all.

His comment was in response to a question of whether there was any justification for Bangabandhu’s home-cum-museum at 32 Dhanmondi in Dhaka being torched by a mob.

The reset remark was deeply upsetting for the country. Obviously, it did not show Yunus in a positive light.

On 8 August, when he was sworn in as Chief Advisor, Professor Yunus formed a council of advisors to assist him in administering the state.

Yunus would have done well to bring into his government individuals with proven records of participation in earlier governments rather than the individuals he inducted as advisors, for the good reason that none of the advisors had ever held a position of significance in any political or caretaker regime.

For Yunus and his colleagues, therefore, it was a situation where they needed to find their way about and around the levers of administration. Adding to the problem was the inclusion of three students as members of the advisors’ council when Yunus could have had them as assistants in his office.

Public worries have lately been voiced over the competence of these students-cum-advisors in running the ministries allocated to them.

An early instance of the Yunus administration being hostage to students manifested itself when, in light of some constructive comments he made on the state of future politics particularly in relation to the deposed Awami League, Brig. Gen (retired) Sakhawat Hossain, advisor for home affairs, was removed from his position and assigned another ministry.

The removal was prompted by students demanding that Hossain, who had in 2007-2008 served as an election commissioner, be removed forthwith. Professor Yunus was unable to assert his authority in keeping Hossain in his original position.

A shortcoming, a serious one, on the part of the interim government, has been its failure to shape strategy for the next general election.

On top of that, it has collected too many items on its plate by setting up no fewer than eleven commissions to carry out reforms in various sectors.

The problem with this approach is that any reforms the interim government suggests will require the approval of a future elected parliament before they can be put into implementation.

The parliament-to-be might consider a good number of these reforms as untenable and thus unacceptable. Besides, questions have been raised about the commission empowered to undertake a reform of the constitution.

Headed by a Bangladeshi-American academic rather than by a constitutional expert from within Bangladesh, the commission appears headed for a wholly new constitution that might change the fundamental character of the secular state established by the constitution promulgated and adopted in 1972.

Human rights have been a casualty in the country. No investigations or inquiries have been initiated into the atrocities perpetrated on leaders and activists of the Awami League at the grassroots level.

Additionally, with policemen reluctant to return to duties owing to the mob attacks on them post-5 August, there has been no move to inquire into the number of policemen killed around the country.

Scores of journalists have lost their jobs, with a good number of them hauled away to prison and unable to get bail. Most political and media detainees have had murder charges slapped on them.

Professor Yunus, assuming that he asserts his authority, could set matters right by ensuring that the rule of law prevails in the country.

Moreover, his administration, as it prepares to hold elections, whenever that happens, should be taking steps from now on toward ensuring that all political parties, including the Awami League, are given the opportunity to campaign freely and without intimidation in the run-up to the elections.

On the diplomatic front, the interim government has been having a hard time. Relations with India, traditionally and historically constructive and friendly since the liberation of Bangladesh, have plummeted to a point where it will need a future elected government to restore the balance with Delhi.

There has been a sudden and surprising resurgence in friendship between Pakistan and Bangladesh, in ignorance of the fact that Islamabad has for the past five decades-plus failed to offer Dhaka any formal apology over the genocide carried out by its army between March and December 1971.

The Yunus government would have done well to undertake detailed investigations of the corruption allegedly indulged in by the Awami League and its supporters and others.

But extending its reach into other areas, such as its decision to remove Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s image from currency notes, were gratuitous moves that only tied the regime into unnecessary knots.

With the BNP and other parties beginning to call for early elections, the political situation will certainly heat up.

ALSO READ: Bangladesh: Waging war on Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

Given the happenings of the last six months, it is today an absolute necessity for an elected government to take charge and inaugurate afresh a journey toward attaining the kind of democracy that has consistently been the national goal since the emergence of Bangladesh fifty-three years ago.