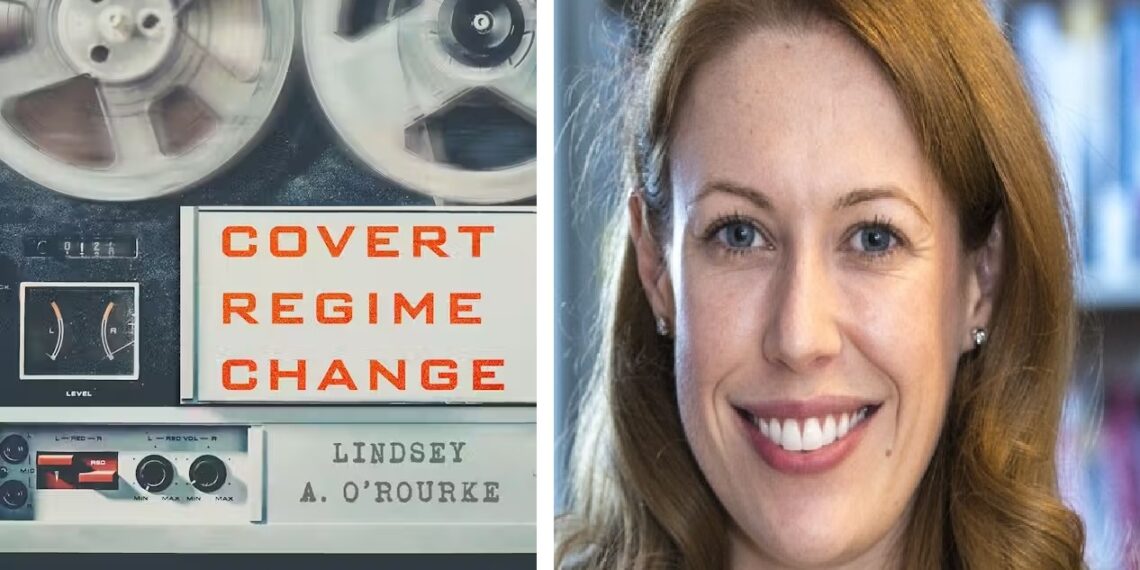

Boston College’s Political Science Department Associate Professor Lindsey A O’Rourke would certainly have added Bangladesh as a case study in her widely acclaimed book Covert Regime Change: America’s Secret Cold War that was published by Cornell University Press in 2018.

Naïve naysayers might continue to contest that the US deep state had nothing to do with the August 2024 regime change in Bangladesh, but O’Rourke’s theoretical framework would certainly be applicable to Bangladesh.

Emphatically claiming that “Regime change is not, however, just a Cold War phenomenon”, O’Rourke goes on to state that “each American administration in the post–Cold War era has embraced regime change, intervening overtly and covertly in places such as Haiti (1994), Afghanistan (2001), Iraq (2003), Libya (2011), and Syria (2012)”.

Providing a rationale for the central thesis in her book, O’Rourke says “this preference for regime change seems unlikely to change anytime soon.

The United States and other great powers will likely continue to undertake both covert and overt missions regularly” and therefore it is important and instructive to understand “how and why states launch these operations”, making it crucial to analyse “the causes, conduct, and consequences of foreign-imposed covert regime change”.

The US driven regime change in Bangladesh had some key features that reflect why “states launch both covert and overt regime changes to increase their security and the security of their allies.

Sometimes this means overthrowing a foreign government that poses a specific military threat; at other times, states pursue regime change to increase their relative military power vis-à-vis rivals”.

O’Rourke suggests “three main types of security interests that drove the United States to intervene”:

- Offensive operations aim to overthrow a military rival or break up a rival alliance.

- Preventive operations attempt to maintain the status quo by stopping a state from taking certain actions—like joining a rival alliance or building nuclear weapons—that may pose a larger threat in the future.

- Hegemonic operations seek to keep target states politically subordinate. In these cases, the intervener is trying to acquire or maintain hegemony over a certain geographic region to obtain the military, political, and economic benefits associated with being a regional hegemon.

Arguing that “regime change holds a unique appeal for policymakers”, O’Rourke says that “regime change allows a state to install a foreign government that shares the intervening state’s preferences and interests. In theory, such a move is mutually beneficial to both parties and has the potential to fundamentally transform the relationship between the two states. If the operation is successful, the new government will share mutual interests with the intervener, meaning that it will then act in the intervening state’s interests”.

In this context, it would be useful to trace US actions that began in the summer of 2023 when the State Department in general and the then American ambassador in Dhaka, Peter Haas, mounted a concerted campaign to pressure the then Sheikh Hasina regime to conduct “free and fair elections” in Bangladesh.

This overt pressure tactic lasted until November 2023. The US maintained a stoic silence till well after the fraudulent January 7, 2024, elections that brought back the Awami League to power for a fourth consecutive term.

The second phase of the US operation began in July 2024, in which university students, teachers and Islamist outfits were used to spearhead a violent movement that finally forced Sheikh Hasina to abandon Gana Bhaban – the prime minister’s residence – to seek refuge in New Delhi.

With the main obstacle in the US’ path vanquished, the American deep state then launched the third phase of its post-regime change operation.

This involved the actual objective – to clandestinely support the Arakan Army, with the full backing of the Mohammad Yunus regime, and utilising the Bangladesh Army as an actor to provide logistics and supplies to the Rakhine State insurgent outfit so it is able to launch a military offensive on three townships in control of the Myanmar military junta.

One convert tactic aimed at regime change, in O’Rourke’s work on several target countries, was “pseudo covert” in nature and which sought to use “democracy promotion”.

In Chile, Haiti, Liberia, Nicaragua, Panama, the Philippines, Poland, and Suriname, O’Rourke writes, “the US government first provided funding to the NED (National Endowment for Democracy), which in turn allocated funds to four “core constituencies”: the American Center for International Labor Solidarity (ACILS), the Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE), the National Democratic Institute (NDI), and the International Republican Institute (IRI)”.

It may be recalled that before Sheikh Hasina was dislodged, both the NDI and IRI played overt roles in the American campaign on so-called “democracy promotion”.

O’Rourke’s remarkable work focuses on the “pseudo covert continuum” in which “On multiple occasions during the Cold War, the United States pursued operations that are perhaps best described as “pseudo-covert”—that is, a regime change operation where the United States officially denied its role even though all parties involved seem to know of its participation”.

O’Rourke observes that “Policymakers pursue pseudo-covert operations for the same reason that they pursue missions that they intend to remain entirely secret: to minimize the predicted costs of the operation”.

However, in Bangladesh’s case, the American “pseudo covert” operation – to first dislodge Sheikh Hasina, followed by its funding to and backing of the students’ movement, installation of the unelected Mohammad Yunus interim regime and now the clandestine support to the Bangladesh Army so that it provides logistics and supplies to the Arakan Army – is now blown.

But, predictably from a theoretical perspective, the Yunus regime will continue to maintain the “charade of pseudo-covert conduct” which “can still minimize the operation’s material, reputational, and security costs”.