Following last August’s civil unrest in Bangladesh, labeled as the ‘Anti-Discrimination Movement’, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina sought refuge in India on August 5, 2024, leaving behind questions about her resignation’s legitimacy.

The movement, led by non-students with hidden financial backing, engendered significant violence, civilian casualties and ultimately the toppling of Sheikh Hasina’s government.

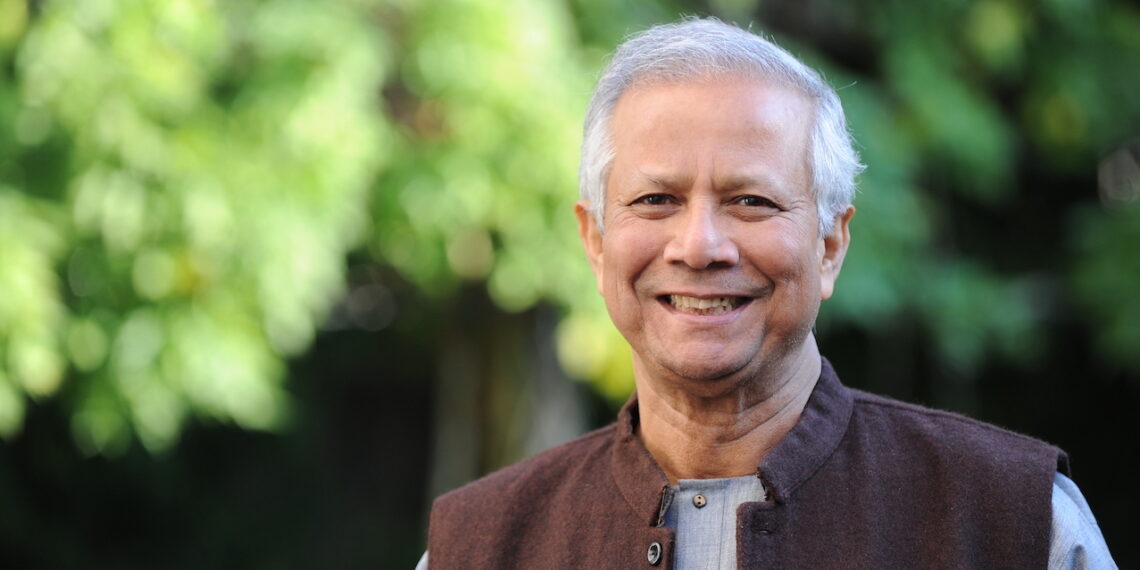

This unrest culminated the formation of an interim government headed by Nobel Peace Laureate Muhammad Yunus.

The legality of this government has been under scrutiny since its inception, given that the Constitution of Bangladesh does not outline provisions for an interim government.

The oath-taking of Yunus’ administration was based on an unclear Supreme Court reference, followed by the resignation of the very judges involved, under mob pressure.

This raised doubts about the military’s behind-the-scenes involvement.

Following the students’ movement, Yunus, the founder of Grameen Bank, was appointed as chief adviser, even though he was charged with tax evasion in Bangladesh. In May 2023, the High Court found him guilty of failing to pay over Tk 12 crore (approximately $1.1 million) in taxes related to donations he received between 2011 and 2013.

The court ruled that Yunus had unlawfully avoided taxes on these funds, which he had transferred to different trusts.

His legal team argued that the donations were meant for social causes and should have been exempt from taxation.

However, Bangladeshi authorities maintained that he was legally obligated to pay.

Yunus was also charged with labour law violations.

In January 2024, a Dhaka labour court sentenced him to six months in jail for failing to distribute a workers’ welfare fund to employees of Grameen Telecom, a non-profit organisation he chaired.

Yunus’ appointment as the chief adviser, despite being under the legal lens, raises ethical concerns regarding governance and public trust.

While Yunus is internationally respected for his contributions to microfinance and poverty alleviation, his conviction for tax evasion and labor law violations at the time of his appointment casts doubt on the ethical integrity of the decision.

Ethical leadership demands that individuals in key governmental positions uphold the highest standards of legal and moral conduct.

Appointing someone with an ongoing legal controversy may undermine public confidence in the rule of law and set a problematic precedent.

However, supporters argue that his global reputation and perceived neutrality in Bangladesh’s political landscape made him a suitable candidate for stabilising the country.

Ultimately, while the appointment may have been legally permissible, its ethical justification remains debatable, especially in a country striving for transparent governance.

The absence of a formal resignation letter from Hasina and the sudden dissolution of parliament by the president raised more constitutional concerns.

Article 57(1)(a) of the Bangladeshi Constitution states that the prime minister’s resignation must be submitted directly to the president.

There is no formal evidence that Sheikh Hasina submitted such a letter, which questions the legitimacy of her resignation.

The dissolution of parliament shortly after Hasina’s departure is viewed as problematic, as the constitution requires the prime minister to advise the president in writing, which reportedly did not happen.

This hasty dissolution is seen as undermining the constitutional process.

The military appears to have played a significant role behind the scenes. Their failure to protect key state institutions including Dhanmondi 32 residence of the father of the nation Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, supreme court premises, residence and office of the prime minister and parliament raises concerns about their real intentions.

While Bangladesh has a history of coups, it is suggested that the military avoided a direct takeover to protect their involvement in UN peace missions, which prohibit forces from coup-governed nations.

Nonetheless, military-backed changes to the judiciary and executive branches indicate an indirect power shift.

Allegations of human rights abuses under Yunus’ regime, including the mistreatment of a former Supreme Court judge, have created fear within the judiciary.

Many hundreds of people have been and are being killed in the name of mob justice, houses and business institutions of oppositions and minority communities are being looted and vandalised, hundreds of temples have been burned down.

The military’s influence over the interim government has deepened concerns about the country’s future political stability.

The interim government’s legitimacy is under heavy debate, especially in terms of international representation, such as at the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). Critics argue that allowing Yunus to represent Bangladesh at the UN would undermine constitutional legality.

(The writer is a practicing solicitor in England and Wales. He was formerly an advocate in Dhaka)