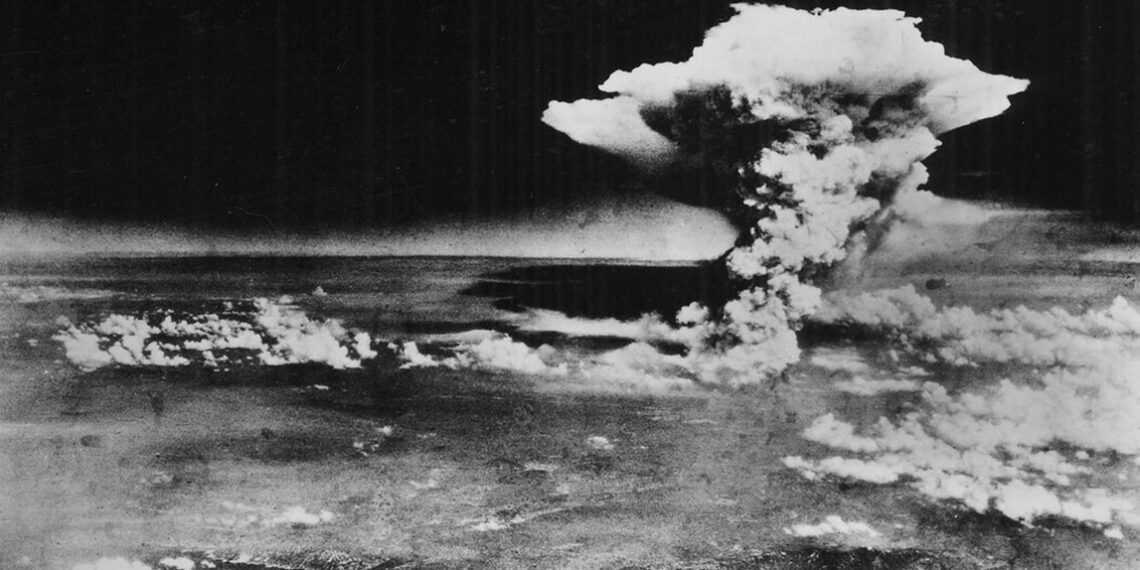

Nearly eight decades after Hiroshima and Nagasaki were devastated by atomic bombs, the voices of those who survived — known in Japan as hibakusha — are becoming increasingly rare.

These survivors, the only people in history to experience nuclear warfare firsthand, have long been central to global anti-nuclear advocacy.

Now, as their numbers dwindle, Japan is finding new ways to ensure their stories endure.

In 2024, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Nihon Hidankyo, the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organisations, in recognition of its relentless campaign and testimony-driven message that nuclear weapons must never be used again.

The award underscored the profound role hibakusha narratives play in shaping the world’s commitment to peace.

But time is closing in. For the first time this year, the number of officially registered atomic bomb survivors dropped below 100,000.

Anticipating this inevitable reality, the Hiroshima city government launched the A-bomb Legacy Successor Programme in 2012.

The initiative trains volunteers to share survivors’ stories and keep their legacy alive when no firsthand witnesses remain.

Volunteers spend two years in intensive training at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

They study the historical context of the bombings, learn public speaking techniques, and work closely with a survivor to craft an accurate narrative.

Each presentation is fact-checked by the museum and approved by the survivor before the volunteer is certified.

Once certified, successors deliver lectures at the museum, in schools, and in communities across Japan.

Yet the effort raises a profound question: Can memories born from trauma truly be conveyed by someone who did not experience them?

Firsthand survivor testimonies are deeply personal, often raw, and can last an hour or more. Successor presentations, however, are more structured. They typically begin with historical background on the Pacific War and the atomic bombings before moving to the inherited testimony, which is presented in the third person and lasts about 15–20 minutes.

The museum also insists on strict accuracy, discouraging language that may be scientifically misleading. For example, a survivor might recall seeing “a woman melting from heat rays,” an emotionally charged description. Successors are instructed to avoid repeating such phrases because, scientifically, a human body cannot melt in seconds. This careful balancing act reflects the programme’s core challenge — honouring emotional truth while maintaining factual integrity.

Traditionally, the authority of a survivor’s story lies in their physical presence — the immediacy of hearing from someone who lived through the unimaginable.

Replicating that emotional impact is difficult. Attendance figures highlight the gap: in 2023, survivors gave 1,578 talks to over 110,000 people, while successors delivered 1,379 lectures but reached only 14,575 attendees.

Still, demand is strong among international visitors, with English-language successor talks accounting for 35% of all such sessions.

ALSO READ: ‘Mekhela Wednesday’ weaves culture, camaraderie at Nagaland University

As the hibakusha generation fades, questions about the successor programme’s future remain unresolved.

Who will validate these stories once no survivors are left?

Will descendants take on that responsibility, or will institutions like the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum oversee the process? These decisions will shape how Hiroshima’s legacy is carried forward.

What is certain is the urgency of the task.

With nuclear tensions and weapons proliferation still present in global politics, preserving the memory of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is not just about remembering history — it’s about ensuring the world never repeats it.