By Shraman Banerjee

On Monday, Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched a Rs 1 lakh crore (US $1.13 billion) Research, Development and Innovation fund to catalyse private sector participation in high-impact R&D. Such projects are also often high-risk, and struggle to attract traditional funding. The fund’s aim is to strengthen India’s capabilities in strategic technologies and promote technological self-reliance.

Global supply chains have been unsettled by the actions of US President Donald Trump on more than 90 countries, but for India — despite being hit by 50 percent tariffs — this need not be an enduring setback. It can, in fact, be an opening.

Tariff walls that restrict global supply chains also create gaps that nimble economies can fill. For India, the way forward is not to shy away from uncertainty but to embrace it through bold experimentation in technology and industrial policy.

This is where the lessons of research on strategic experimentation become crucial.

A recent paper by researchers at Shiv Nadar University, including this author, examined how decision-makers choose between safe, predictable options and risky, uncertain ones that carry the promise of much higher returns. The “safe arm” provides steady but limited gains, while the “risky arm” may lead to costly failures, or to breakthroughs that permanently raise payoffs.

What matters is not just the outcome of today’s choice, but the knowledge it generates for tomorrow. By experimenting, actors learn about the true state of the world; by avoiding risk, they remain in the dark. The paradox is that even apparent failures can be productive, because they update our beliefs and sharpen future decisions.

This framework, often called strategic experimentation in economics, helps explain why bold risk-taking can be rational even in uncertain environments. This logic is directly relevant to India’s present crossroads.

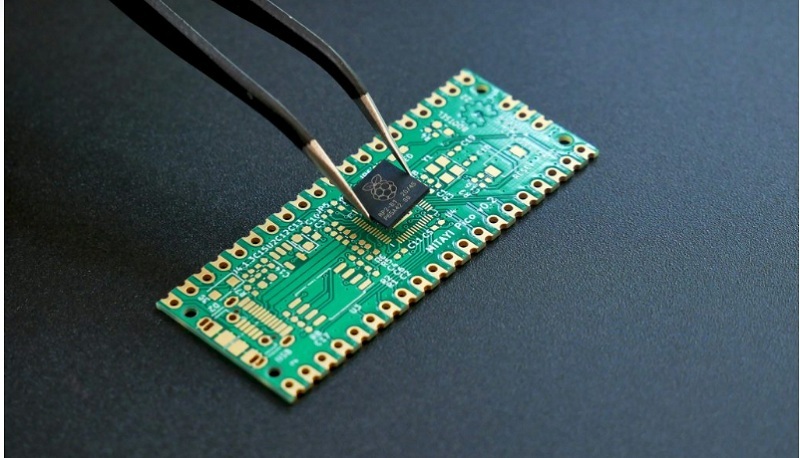

Should we build domestic semiconductor fabrication units or “fabs”, knowing some may falter? Should we allow artificial intelligence (AI) startups to test applications aggressively, even if regulations must later adjust? Should we bet on electric vehicles despite current bottlenecks in charging networks and costs?

Not experimenting may be costlier

Each of these is a risky path — but one that generates information, skills, and institutional learning. In a world where geopolitical rivalries disrupt supply chains, the cost of not experimenting may be greater than the cost of failed experiments.

India’s own history bears out this truth. Universal suffrage at independence was itself an audacious experiment for the country, as was its early engagement with planning and non-alignment — an act of faith in democratic participation and self-reliance at a time when much of the world doubted that either could thrive in a poor, newly decolonised nation. Extending the vote to every adult, regardless of literacy or wealth, was a political gamble on mass participation.

Non-alignment, too, was a strategic gamble — choosing independence of judgment over the security and aid that came with joining either superpower bloc. Not every gamble succeeded, but each attempt shaped institutions and capacities that endure. Today, our tryst with the future demands a similar willingness to learn by doing.

The danger is that failures are visible while the knowledge they produce is invisible. A semiconductor fab that struggles or an electric vehicle (EV) subsidy that overshoots budgets attracts criticism. But less obvious are the foregone benefits of never trying at all — the engineers who were never trained, the supply chains never developed, the regulatory frameworks never stress-tested.

Recent research at Shiv Nadar University and the broader economics literature on strategic experimentation shows that these ‘invisible costs of caution’—the opportunities lost by not taking risks—can outweigh the costs of failure.

What does this mean for policy? It means India must treat experimentation not as an accident but as strategy. Regulatory sandboxes that allow AI applications to be tested in controlled settings; mission-driven semiconductor projects that tolerate some waste in exchange for capability-building; innovation zones where startups can fail without stigma — these are not indulgences, but investments in learning. The question for policymakers is not whether every project will succeed. It is whether each project leaves behind knowledge that makes the next attempt more likely to succeed.

Trump’s tariffs make this reality starker. As global trade fragments, nations are being pushed to localise production in strategic sectors, a shift highlighted in recent IMF World Economic Outlook and WTO Global Trade Outlook reports. India has a chance to step into this breach — but only if it is willing to shoulder uncertainty and accept missteps along the way. The semiconductor race, the push for AI, the EV transition: none will follow a straight line. The winners of this century will not be those who avoid mistakes, but those who learn fastest from them.

To succeed, India must reframe what it means for policy to “work.” Short-term outcomes matter, but so does long-term knowledge accumulation. Each failed attempt is tuition for the next success. Risk-aversion may win applause in the moment, but it leaves us unprepared for the shocks and opportunities of an unstable global order.

If the twentieth century was India’s tryst with destiny, the twenty-first must be our tryst with experimentation. The question is not whether India can avoid uncertainty – it cannot. The question is whether we can harness it to leap ahead.

Shraman Banerjee teaches Economics at Shiv Nadar University.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.