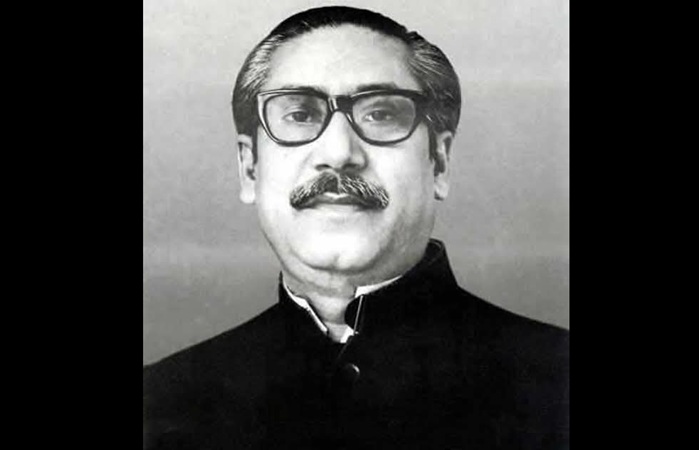

A half century after his assassination, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman remains an individual of whom anti-historical elements in Bangladesh remain afraid. Those who seized power in the country in August last year have unabashedly presided over the conspiracy to destroy his heritage through destroying his home.

Not one of these people in the current unconstitutional regime, among whom are those who have been freedom fighters or are privy to having witnessed their family links with Bangabandhu and with the War of Liberation, have had the moral courage to condemn the organised vandalism which has gone into acts that speak of sedition or high treason.

Indeed, in their silence they have only egged on the mobs that have in the past fifteen months laid Bangladesh low.

A few years ago, the acting chairperson of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party repeatedly spewed venom against Bangladesh’s founder by floating the ludicrous idea that the Father of the Nation had flown from Pakistan to Britain after his release from incarceration in January 1972 on a Pakistani passport.

He and his cohorts did not stop there, but went on to spread the canard that not Bangabandhu but General Ziaur Rahman was Bangladesh’s first President.

Conveniently overlooked was the fact that when Zia, at the time a major in the Pakistan army who had opted to revolt as the genocide by the Pakistan army got underway in March 1971, announced his message of independence, he did so in the name of ‘our great national leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.’

These days, a clutch of non-descript individuals, some of them allegedly retired military officers, have been going around spreading the sophistry that Bangabandhu was not around during the War of Liberation and hence had little idea of the sufferings the nation was put through.

These little men, for that is what they are, have little idea of history.

They have little understanding of the politics of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Or they are engaged in a vicious campaign to vilify him.

And yet Bangabandhu remains the single most potent symbol of Bangladesh’s history. The truth is that his enemies have always lost in their struggle against the image of Bangabandhu.

There are all those men and women who have consistently, and without embarrassment, taken perverse pleasure in undermining Bangabandhu, both when he was alive and all these years since conspiracy caused his assassination.

There is quite something to be said about those Bengalis who somehow cannot rest easy with the place of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in history.

In the 1980s, Syed Najmuddin Hashim — civil servant, diplomat and eminent scholar — enlightened yours truly with remarkable tales of some Bengali civil service officers trapped in Pakistan in the aftermath of Bangladesh’s battlefield triumph in late 1971.

Dismissed from service by the government of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and placed in discrete camps all over Pakistan, these Bengali officers spewed venom against Bangabandhu and even made the dire prediction that his new country would soon return to the fold of Pakistan.

These men had, after all, lost their cushy jobs and did not quite relish the prospect of working for a country that had till recently been a mere province of the state that now was disowning them.

And yet the irony is that these very men came home to Bangladesh and rose to high positions.

They proved relentless, though, in their antipathy towards Bangabandhu.

That only reminds you of the Bengali officer in Pakistan’s foreign service stationed at the Pakistan mission in Delhi in 1971.

On his annual leave he did not go to ‘East Pakistan’ but travelled to West Pakistan, where he quarrelled with other Bengalis and rudely described the Bengali liberation struggle as a conspiracy against Pakistan.

You only have to read the late General Khalilur Rahman’s book to go into the details.

He later became a valued ‘Bangladeshi nationalist’ in the BNP, rising to the position of a minister of state.

There is then the tale of a brother of an intellectual murdered on the eve of victory in 1971.

He agreed with his Pakistani friends that Bangabandhu was ‘destroying’ the Muslim country that was Pakistan.

When he first received news that his sibling had been kidnapped and killed in Bangladesh on the eve of its liberation, he quickly blamed the Mukti Bahini for the tragedy.

He lapsed into stupefied silence when it swiftly became known that it was the al-Badr, the collaborators who had served as the quislings of the army he was serving, that had murdered his sibling.

In independent Bangladesh, we have had precious little dearth of Bangabandhu baiters.

A retired military officer once stranded in Pakistan and who rose to a high perch in the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (before subsequently being sidelined as a reformist in caretaker times) informed a relative without shame at a point that he did not regard Sheikh Mujibur Rahman as Bangabandhu.

It did not occur to him that the peaks he had climbed after 1971 all had to do with the politics Bangabandhu had pursued in his career. This man retired as a general in the Bangladesh army.

Had Pakistan survived in these parts, he would have retired as a lieutenant colonel at most. And those civilians Hashim spoke about would, minus Bangladesh, have gone into superannuation as mere section officers.

Ziaur Rahman had no hand in the murder Bangabandhu, sure. But he knew about it and kept quiet.

That was an indefensible act, concealing information that your President is about to be murdered by men you hobnob with.

The Zia regime made sure that Bangabandhu was airbrushed out of history.

In the Ershad period, more humiliation was piled on Bangabandhu, on all of us, when the killers of the nation’s founder were allowed the privilege of forming a political party and taking part in elections.

The fact that the process of the trial of Bangabandhu’s assassins was halted soon after the BNP-Jamaat alliance found itself in power in 2001 was a fresh demonstration of the animosity with which the ‘Bangladeshi nationalists’ and the old defenders of Pakistan looked upon Bangabandhu.

There have been all the Bangabandhu-haters who, without shame, have kept beating the drum about Bangabandhu having surrendered to the Pakistan army and gone away to Pakistan in March 1971.

These are men who either do not understand the lessons of history or deliberately ignore them. Their pathological hate for Bangabandhu colours their politics, if that is politics at all.

Go beyond these political spaces. There have been journalists in Bangladesh who do all they can to strike at Bangabandhu’s stature.

Erstwhile pro-Peking elements (and you have journalists among them too) will give you long so-called dialectical arguments on how Bangabandhu and the Awami League ‘commandeered’ the liberation struggle just when these leftists were about to bring freedom to our people.

The fact is that leftists like Abdul Haq were in 1971 busily engaged in subverting the Bengali cause.

Their continued links with Pakistan, as late as in 1974, remain proof of their perfidy.

There are newspapers in this country which have taken asinine pride in refusing to accord Bangabandhu his place in history. For the men behind these publications, Mujib has never been Bangabandhu.

You double over with laughter when you see the pains these men go through when they refuse to accept the official term of the August 1975 killers’ trial as the Bangabandhu murder trial and instead continue to call it the Mujib murder trial.

For these men, Bangabandhu was no higher than being President of Bangladesh. And the four national leaders murdered in prison in November 1975 were no more than four Awami League leaders.

The Zia acolytes have gone about propagating the false narrative that the nation’s first military ruler initiated a multi-party system in the country.

Observe: that multi-party system opened the doors to communal politics, allowed the collaborators of the 1971 Pakistan occupation army into politics in independent Bangladesh and unabashedly foisted ‘Bangladeshi nationalism’ on the country.

There were the veteran politicians, Bangabandhu’s contemporaries but without his principles, who after 15 August felt no compunction in celebrating the day of Bangabandhu’s death as ‘najat dibosh’ — deliverance day.

Those politicians are forgotten today, consigned to the dark depths of history, having pursued a raucous career based on opportunism and unnatural animus toward the Father of the Nation.

All those who spend their waking hours vilifying Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman travel on passports they came by through his determined leadership of his people.