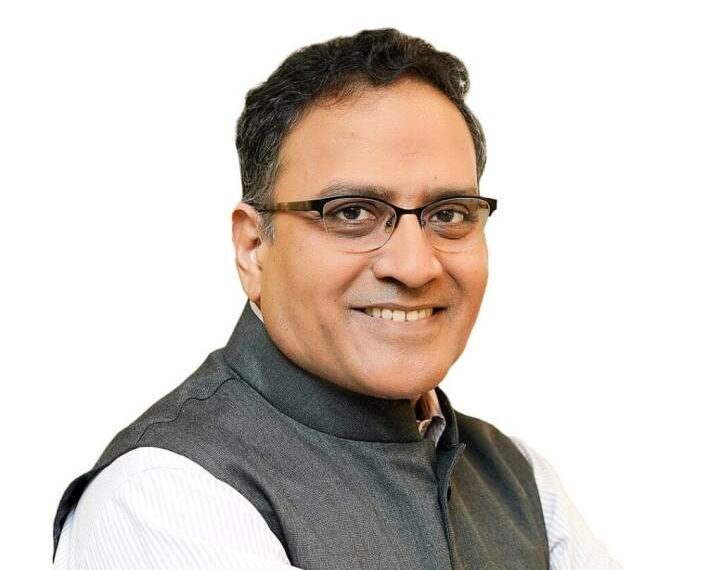

Climatic disasters have been a bane in hilly areas, be it the recent Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh fatal cloudbursts or a series of catastrophic incidents in the Northeast. How does it reflect on the minds of people at the receiving end? Here’s former bureaucrat Dr. Indu Bhushan and founding CEO Ayushman Bharat spelling it out in a candid chat. Excerpts:

How do you connect climate-related disasters and the ongoing economic downturn with mental health?

Climate-related disasters and the ongoing economic downturn are creating a perfect storm for mental health. Floods, cyclones, and heatwaves leave deep emotional scars, triggering anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress. The loss of homes, livelihoods, and community stability adds to the strain. Economic shocks make matters worse. Job losses, income insecurity, and rising living costs erode resilience and prolong mental health struggles. In rural areas, crop failures linked to climate change have increased farmer distress. In cities, economic hardship and displacement create new layers of stress. These crises overlap and persist, overwhelming coping mechanisms and stretching already under-resourced mental health systems. Urgent, integrated action is needed to address both environmental and economic threats to well-being.

The recent spate of landslides in Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh has been catastrophic. How do you perceive their repercussions on the mind?

The recent landslides in Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh have left not just physical devastation but deep psychological wounds. For many, the sudden loss of family, homes, and livelihoods has been a shattering experience, bringing acute trauma and grief. Displacement and uncertainty about the future weigh heavily, while the destruction of local economies adds layers of chronic anxiety and depression. Children may carry lasting fears of rain or travel on mountain roads, and older residents mourn the loss of landscapes that defined their lives. In these fragile Himalayan regions, where mental health services are limited, the emotional aftershocks could persist long after roads are rebuilt and houses restored—unless recovery efforts place mental well-being at their core.

Is it more psychological?

Indeed, the psychological effects of natural disasters are frequently just as crucial as the physical ones, and occasionally even more. Beyond the visible destruction, survivors face deep emotional trauma, persistent anxiety during rains, and grief over lost homes and livelihoods—effects that can last far longer than the physical rebuilding.

Isn’t it an irksome job for mental health doctors to suggest a remedy?

It is certainly challenging, because the distress after such disasters is layered—trauma, grief, economic loss, and uncertainty all overlap. Mental health professionals must work with patients who may be reluctant to seek help, have lost support networks, or face continuing environmental risks. The remedy often requires not just counselling or medication, but community-based support, rebuilding trust, and restoring a sense of safety—tasks that go well beyond the clinic.

How equipped are we to handle such a problem?

We are not very well equipped to handle such large-scale, disaster-related mental health needs. We have fewer than one mental health professional per 100,000 people—far below the WHO’s recommended minimum—and services are concentrated in urban areas, leaving disaster-hit rural and hilly regions with minimal access. While initiatives like the District Mental Health Programme and tele-mental health services are steps forward, they are not yet scaled to respond rapidly to mass trauma. In reality, our ability to cope depends heavily on community resilience, NGOs, and ad-hoc volunteer efforts, rather than a well-integrated, adequately resourced mental health disaster-response system.

What is the way forward, keeping in mind that natural disasters are not in our hands?

While we cannot prevent natural disasters, we can greatly reduce their psychological toll by making mental health a core part of disaster preparedness and response. This means training local frontline workers in psychological first aid, deploying rapid-response counselling and tele-mental health services, restoring livelihoods quickly through cash or job support, and creating safe spaces for children and communities to process grief. Integrating these measures into standard disaster management plans will help ensure that emotional recovery goes hand in hand with physical rebuilding.

Talking of the climate crisis, international deals seem to be only big talks and nothing else. Your take.

Indeed, there is a wide gap between climate-related commitments and real progress. International climate agreements often sound ambitious, but too often they remain lofty declarations without binding action, financing, or enforcement. The recent policy reversals under Donald Trump— rolling back U.S. climate commitments and promoting fossil fuels—have further exposed how vulnerable these deals are to political shifts. As one of the world’s largest emitters and a key driver of climate finance, the U.S. disengagement weakens global resolve and gives cover for inaction elsewhere.