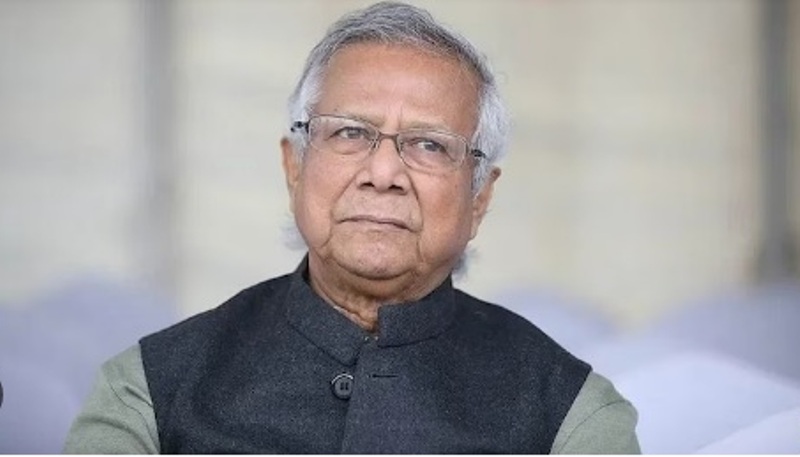

Bangladesh’s interim authority, led by Chief Adviser Mohammad Yunus, appears to have adopted a new tack aimed at building a covert link with the Arakan Army, by taking the plea now that “famine-like conditions” prevail in the Rakhine State, where people are “starving”.

Dhaka’s pitch for a humanitarian corridor is predicated on an ostensible imminent threat of severe famine in the Rakhine State, a move which would enable it to provide logistics and supply support for UN aid to the region in Myanmar that the Arakan Army is seeking to take full military control over.

However, Indian analysts focused on Myanmar and Bangladesh said that while there are mostly United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) reports on severe famine-like and imminent “starvation” conditions in the Rakhine State, in reality, there are shortages of fuel, seeds and fertilisers in the region.

Well-placed Dhaka-based government sources and political analysts said that the Yunus-led interim authority’s aim now appears to have adopted a stand that the aid/humanitarian corridor is to mitigate the adverse impact of “famine-like conditions” in Myanmar rather than support for the repatriation of hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees living in camps in Cox’s Bazar.

The interim authority’s primary condition for the movement of aid and humanitarian support for the Rakhine State was assured conducive environment in that region that would permit the transportation and distribution of aid in the Myanmar region.

There are reports that the Myanmar military junta has put in place some restrictive measures in territories under its control, which have prevented the movement of essential supplies to the Rakhine region. Besides, supplies have been hit as a consequence of the recent devastating earthquake in regions other than the Rakhine State, which was largely unaffected.

UN agencies and organisations have been voicing concerns about an “unprecedented disaster” in the Rakhine. In November 2024, the UNDP said that such an eventuality could be an outcome of a “combination of interlinked issues” such as “restrictions on goods entering Rakhine, both internationally and domestically”.

This, the UNDP said, has “led to severe lack of income, hyperinflation and significantly reduced domestic food production”. Also, “essential services and a social safety net are almost non-existent, leaving an already vulnerable population at risk of collapse in the coming months,” the UNDP report cautioned.

However, informed Indian officials aware of the reality in Myanmar disclosed that representatives of the Kachin Independence Army, Arakan Army and the Chin National Front (CNF) “keep seeking all kinds of things, including seeds, medicines and fertiliser, from us”.

In this context, the officials said that about two-and-a-half months ago, the representatives of these three outfits met policymakers in New Delhi separately to impress upon them the need to get support in the form of the supply of seeds and fertiliser for the Rakhine region.

“India has been trying to fulfill these demands in a limited way,” an official said, even as there are reports that fuel, mainly petrol, is transported via “informal routes” and border points in Mizoram and onward to Chin State in Myanmar.

Other Indian analysts said that “it is not so much famine-like conditions as much as it is shortage of seeds and fertilisers, especially in the cropping season in the Rakhine State”, that is of concern to the Arakan Army.

They wondered why the Bangladeshi authorities, especially the country’s newly-appointed National Security Adviser Khalilur Rahman, should now shift focus from Rohingya repatriation to “humanitarian aid” that they would prefer to “support”. Rahman was reported to have made a statement on Bangladeshi media reported on April 30 that the UN’s humanitarian aid would “help stabilise” and “create conditions for Rohingya repatriation”.

However, Bangladeshi security service sources and other analysts are not ruling out Dhaka’s efforts to push “non-lethal” supplies into Myanmar through the aid/humanitarian corridor that was initially ostensibly meant for the return of Rohingya back to Maundaw and Buthidaung, two locations in the Rakhine State from where the Rohingya were driven out in 2017 and as recently as December 2024 when some of the townships fell to the Arakan Army.

What has made the so-called Rohingya repatriation now a murky issue is the covert support for a passage (to Myanmar) to move non-lethal supplies to the Rakhine State, where the Arakan Army controls 14 or 17 townships.

This, Bangladesh government sources said, was “in line with the objectives of the US-inspired Burma Act”, but did not rule out the movement of “lethal” cargo when the Arakan Army begins its military assault on the yet-to-be captured Sittwe, Kyaukphyu and Manaung townships.