The policy of imposing the Assamese language on the non-Assamese population of the state has created an environment of conflict, which has not been beneficial for the state.

A section of politicians, in an unanticipated move, caused significant harm to the state by pursuing this course.

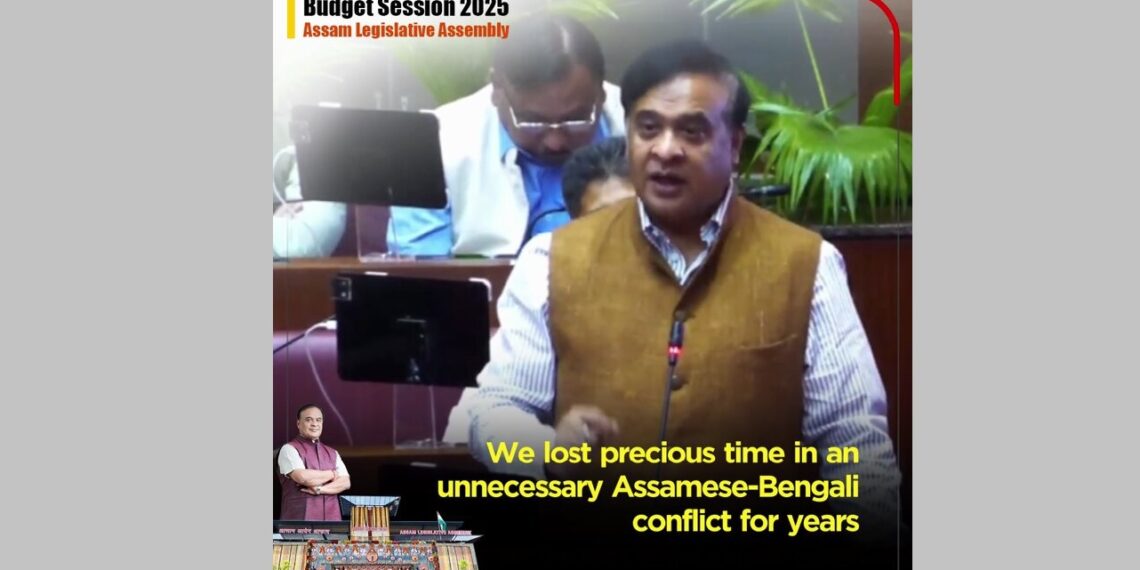

Recently, Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma highlighted that linguistic disputes were primarily responsible for the conflict between the Brahmaputra Valley and the Barak Valley.

Though delayed, his realization on this matter makes him deserving of praise. Recognizing the true cause of the issue, his statement conveys a message of reconciliation.

To make Assam a progressive state, it is crucial to break the barriers of linguistic division and allow the broader Assamese community to emerge.

The work initiated by the cultural icon Bishnu Prasad Rabha was later sabotaged by the machinations of certain radical nationalist forces.

This paved the way for creating an environment of conflict between various ethnic and linguistic groups, as well as the Bengali population of the Barak Valley.

The political complexity that arose from keeping this conflict unresolved has only harmed the larger Assamese society rather than benefiting it.

True intellectuals are now realizing the consequences of these hasty decisions. Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma, a responsible individual and thinker, has made his stance clear through his statement on linguistic conflict.

His underlying objective, which is to move the state towards progress, is something I personally feel grateful for and cannot refrain from acknowledging.

Now, let’s look at how linguistic conflict is created. There is no doubt that the ruling party of the time played a major role in creating this conflict.

Efforts to implement a one-language policy in Assam began as early as the beginning of 1958. On October 24, 1960, the Language Act was passed in the Assam Legislative Assembly.

This law clearly stated that the Assamese language would be the sole language used throughout Assam. Prior to this, the historic language conference held in Silchar, where various communities had collectively passed a proposal, was ignored.

The members of the Legislative Assembly at the time paid no heed to the protests of the leaders of Assam’s hilly regions. In effect, this day marked the sowing of the seeds of separation in the Assembly.

By recognizing Assamese as the only official language of the state, the law paved the way for the imposition of the Assamese language in areas like Goalpara, which had previously been part of West Bengal.

Leaders from the hilly regions became worried, and opposition to Assamese dominance grew in regions such as Garo Hills, Khasi Hills, Jaintia Hills, Naga Hills, Manipur, Lushai Hills, and others.

Although to a limited extent, protests also spread to areas like Karbi Anglong and the North Cachar Hills. No one was able to accept the decision to disregard the views of the indigenous tribes.

This led to a strong reaction in the then-undivided Cachar. Following the passing of the Language Act, a language movement emerged in the Barak Valley.

The movement, which spread in demand for the protection of the right to use their mother tongue, was supported by various communities in the region, including Manipuri, Bishnupriya Manipuri, tea tribes, Naga, Khasi, and other ethnic groups.

When the language movement intensified, on May 19, 1961, 11 satyagrahis were killed by police bullets at the Silchar railway station.

Though the Mehrotra Commission was set up in response, its report has never been made public to this day.

Additionally, the government has yet to officially recognize the 11 satyagrahis as martyrs.

However, after this movement, the government was forced to withdraw the controversial Language Bill.

Again, in 1972, the Assam Secondary Education Board issued a language circular that mandated the use of Assamese as the sole medium of instruction across the state.

This one-language policy led to widespread protests across Assam. Various organizations united under the demand for a four-language formula.

Along with the Bengali-speaking people of Assam, speakers of Bodo, Karbi, Dimasa, and other tribal languages also joined the movement.

Meetings and gatherings were held in different parts of the state to register their protest. The Bengali leaders of the Brahmaputra Valley strongly opposed this circular.

Due to the intensity of the protests, the government was forced to retreat. The circular issued by the Secondary Education Board was withdrawn, and the government’s one-language policy failed.

During this time, the leadership of the Bengali-speaking leaders in the movement against the language policy saw the rise of radical nationalist forces in Assam, which sought to foster anti-Bengali sentiment.

They began preparing ways to harass and target the Bengali community. Following the example of the British colonizers, the ruling party of the time applied the “Divide and Rule” strategy to retain power.

As a result of the dominance of some politicians, the Khasi Hills and Garo Hills districts were separated from Assam to form the independent state of Meghalaya.

Similarly, the Naga Hills district became a centrally governed state, Nagaland, and the Lushai Hills district was formed into Mizoram.

Prior to this, Manipur and Tripura were given the status of centrally governed territories. These areas are now separate states.

While the Barak Valley was the birthplace of the movement for a separate state, it failed to gain the status of a centrally governed territory.

There are many reasons for this, but there is no opportunity to discuss them in this context.

The largest social organization in Assam is the Assam Sahitya Sabha. This organization is not only connected with the Assamese-speaking community but also with various indigenous groups in the state.

Therefore, in creating an area of coordination, Assam Sahitya Sabha must take important steps. The government can, if necessary, provide patronage to this organization.

Assam Sahitya Sabha can take the initiative to meet and collaborate with the Assam Bengali Sahitya Sabha, the All India Bengali Literary Conference, the Barak Valley Bengali Literary and Cultural Conference, the International Bengali Language Conference, the Karbi Sahitya Sabha, the Bodo Sahitya Sabha, the Nepali Sahitya Sabha, the Dimasa Sahitya Sabha, as well as other social organizations of smaller communities.

Through such meetings, the scope for coordination can be expanded. Assam, being a multilingual state, cannot hide this truth.

Therefore, a prosperous Assam needs to be built with all linguistic communities. No form of division or hatred should be nurtured; everyone must move forward with an open mind.

To achieve this, efforts should be made to develop a trend of bringing people from Lower Assam to Upper Assam, Upper Assam to the Barak Valley, and people from the Barak Valley to various parts of Northern Assam for meetings and conferences.

The central session of Assam Sahitya Sabha can be organized in the Barak Valley. Initiatives can be taken to centrally celebrate the birthdays of Bishnuprasad Rabha and Lachit Barphukan in the Barak Valley.

Similarly, the birth anniversary of Arun Kumar Chanda, a pioneer of Assam’s labor movement, can be celebrated in some part of the Brahmaputra Valley.

Events like Jhumur Binandini, where artists from all over the state perform, can be organized in smaller scales in various regions.

There should be arrangements for various tribal communities’ cultures to be seen and understood by others. Such events will bring people together, naturally eliminating thoughts of division and fostering a spirit of unity.

By creating a bridge of coordination between language and culture, people’s daily lives can be enriched, changing their mindset in a positive direction.

To build Assam as a leading state, the cultural heritage must be highlighted alongside the socio-economic conditions, creating a vast area for coordination.

Only then will attempts to create conflicts be eliminated from this region. I hope that, along with political leaders, the state’s true intellectuals will come forward with an open mindset.

In the current time, creating an environment of conflict to block development is not possible. The situation now paves the way for people to be motivated by national consciousness.

Moving forward along this path will bring about the development of the state, progress, and the creation of an environment of peace and harmony.

For this, a narrow mindset must be eliminated, and an open, liberal attitude must be embraced.

The movement centered around language rights led to the formation of a separate Bodoland Territorial Council in the Bodoland area.

As a result of the prolonged struggle, the Bodo language has been granted official status.

Currently, Bodo has been accorded the status of an associate official language in Assam. This step has undoubtedly succeeded in reducing the mental distance between the Assamese and Bodo communities.

In the Barak Valley, Bengali has been granted the status of an official language of the state. Additionally, in three districts of the state, Manipuri has been given the status of an associate state language.

These steps have contributed positively to fostering unity and harmony in the state. The government is actively considering giving other indigenous languages the status of mediums of instruction in schools.

This is certainly a matter of great joy, as it is natural for a person to receive the best education in their mother tongue.

These steps are being taken by the government, and the current leaders are striving to create a stable atmosphere in the state by guiding themselves on the path of correction in the study of history.

However, government action alone cannot be the only solution. Social organizations also need to be involved in this effort.